Heinlein, Robert A. "By His Bootstraps." Astounding Science-Fiction, October 1941.

This article is part of my attempt to read all the 155 stories currently (as of 1 November 2022) on the ISFdb's Top Short Fiction list. Please see the introduction and list of stories here. I am encouraging readers to rate the stories and books they have read on the ISFdb.

ISFdb Rating: 8.71/10

My Rating: 6/10

"Bob Wilson did not see the circle grow."

|

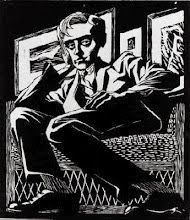

| Heinlein's "By His Bootstraps" was chosen for the cover of ASF October 1941 |

Bob Wilson has locked himself in his room in order to complete his graduate thesis, disavowing the notion of time travel, when his future self appears through a time gate. This future self, referring to himself as "Joe," urges Wilson to step through the gate, claiming that a great future lies ahead. Wilson, sleep-deprived and irritable, is unable to recognize his future self and refuses to comply, when a third version of himself appears. This third version is from a farther future, and refutes the second incarnation's claims. The three selves get into a brawl, and Wilson is conveniently shoved through the gate, because otherwise we would not have much of a story.

On the other side, Wilson encounters Diktor, the controller of the time gate, who claims Wilson has stepped 30,000 years into his future. He informs Wilson that the gift of the time gate was bestowed to humanity by a race of aliens referred to as the "High Ones," who essentially enslaved humanity and transformed them into meek creatures. Here, among the spineless humans of the future, Wilson could make himself king.

A great concept raising many paradoxes of time travel, as Heinlein frequently did (see " 'All You Zombies...' "). Interesting as an idea, but as a story it is overlong, tiresomely repetitive and predictable. In addition, I don't care for the jocular tone, which worked better for a story like "--And He Built a Crooked House" published the same year (perhaps Heinlein was in that mood at the time) and both published in Astounding Science Fiction (perhaps editor John W. Campbell was in the mood for such hilarity). It worked in Crooked because of the absurd scenario and caricatures, but this story aims to be more complex with more serious undertones, and the light tone is not helped by the story being flat-out unfunny (arguably dated--again a "perhaps" as in 1941 some readers may have gotten a kick out of beautiful enslaved girls who can be owned and traded by men who do not give a thought to anything other than their physical appearance). None of this is helped by the story's protagonist who is conveniently not too smart (despite attempting to write a seemingly complex thesis) and therefore easily manipulated.

"By His Bootstraps" was published in the October 1941 issue of Astounding Science-Fiction, under the byline Anson MacDonald. It was the lead story, a novella, and shared the issue with another novella by Heinlein, "Common Sense," so that of the 164 pages of that issue, 73 of them were from Heinlein's typewriter. "Bootstraps" proved in the long term to be more popular, and since it is a recognizable Heinlein story, it is interesting that it was printed under a pseudonym and not reserved for another issue. I have not read "Common Sense," and it appears to be more recognizable as the second half of the novel Orphans in the Sky, and while the first half, "Universe," had already been published in ASF in the May issue of that same year, as a sequel "Common Sense" needed to carry Heinlein's name. The cover, as well as the interior art accompanying the novella, were produced by Hubert Rogers. The cover illustration depicts the time gate with the three versions of Wilson, and in the backdrop the two different time periods in which he settles.

For more of this week's Wednesday short stories, please visit Patti Abbott's blog.